That's what I said, isn't it? I said it is not the norm today, but it is used in certain dialects. African American Vernacular English and Cockney), although its usage in English is often stigmatized. Standard English lacks negative concord, but it was normal in Old English and Middle English, and some modern dialects do have it (e.g. While Latin and German do not have negative concord. Also, I friggin' love comparative analysis. This relates to what I said about mathematical logic not being useful for explaining how features of languages function.

Now, you probably didn't want quite as much detail for this first part, but I wanted to illustrate how the double negative is perfectly functional in languages where it is used, and not at all an a priori confusion-inducing.

USING DOUBLE NEGATIVES FULL

Like in biology, to make full sense of a contemporary situation, to understand why the laryngeal nerve goes as it does so to speak, you often have to dig into its evolution. Language history is a fascinating subject. This is because, historically, they weren't. *You may have noticed that some of the negative elements in French don't look like negatives (personne, rien). This is commonly used in speaking, but is considered incorrect (or, let us say, subnormative). You'll notice only one element of negation (the first element is omitted). In French, you would say Je ne l'ai jamais vu.) Interesting comparative detail I've just become aware of. (Although in Portuguese, this doesn't work with "never" - Nunca o vi. In most cases, the double negative comes into play when several elements in the sentence are negated:

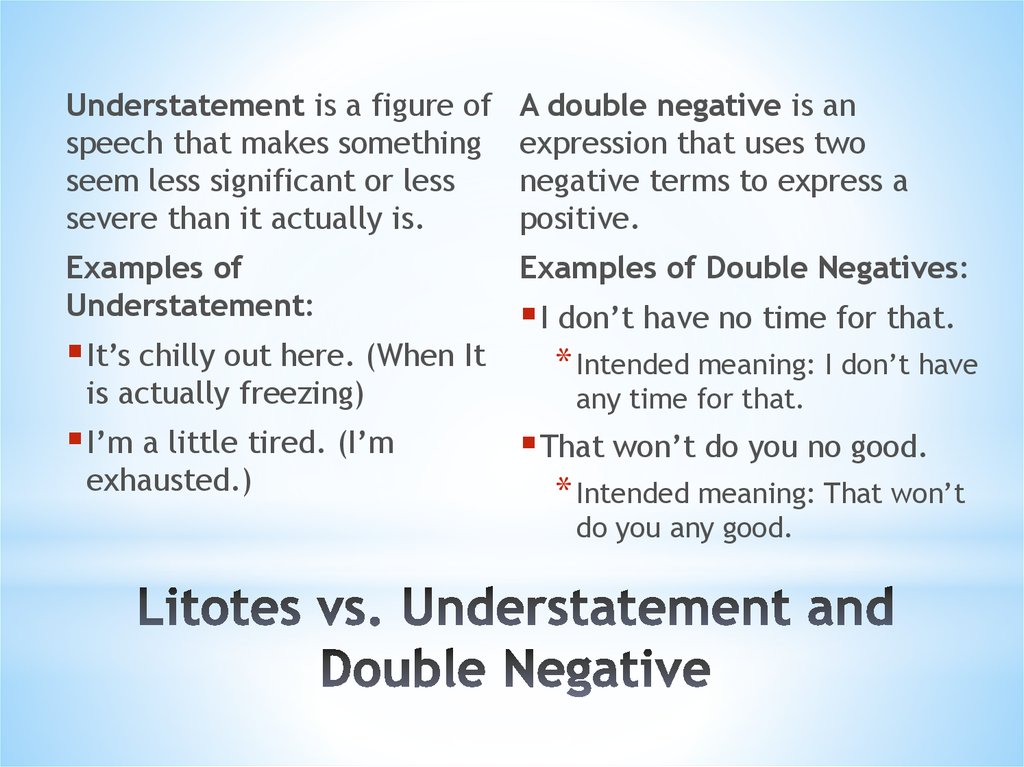

This is a particularity of French (and I think Catalan) - you even need double negative to just negate the verb. contrast this with Portuguese - Não sei - or Slovenian - Ne vem. I don't know about Persian, but in French, Portuguese and Spanish (and in my mother tongue, Slovenian, as well as most other Slavic languages), double negative is grammatically correct and required (in the standard language), although just how it is applied differs across languages. In fact, it is not quite correct to say that double negatives always intensify the negation - they simply express it fully. Portuguese, French, Persian, and Spanish are examples of negative-concord languages, Languages where multiple negatives intensify each other are said to have negative concord. In most logics and some languages, double negatives cancel one another and produce an affirmative sense in other languages, doubled negatives intensify the negation. Multiple negation is the more general term referring to the occurrence of more than one negative in a clause. Wiki wrote:A double negative occurs when two forms of negation are used in the same sentence. Hammers are useful, but for screws you need a screwdriver.Ĭan you actually support this, or am I just to take your word for it? Using mathematical logic to explain certain things is about as helpful as trying to use a hammer to loosen a screw. Hack, it helps if you see languages for what they are - evolved, heterogeneous entities whose properties are explicable by their history. In modern English, the double negative is outside of the norm (there are precise historical reasons for it), but it is still commonly used and understood in a number of dialects. It USED TO BE a standard way (not THE standard way as far as I know) in English, and in fact you can still find it in Shakespeare, where it simply expresses stronger negation than a single negative. The double negative is the STANDARD and CORRECT way of expressing negation in many languages. The difference between the two sentences is sociolinguistic - they convey different information about the speaker's social background and/or the situation of communication (its level of formality).

No it doesn't, because 'I ain't got none' contains a double negative, conveying the information that you do indeed have some (of what, who knows, but certainly not any linguistic ability). "I ain't got none" still conveys the same information as "I do not have any"

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)